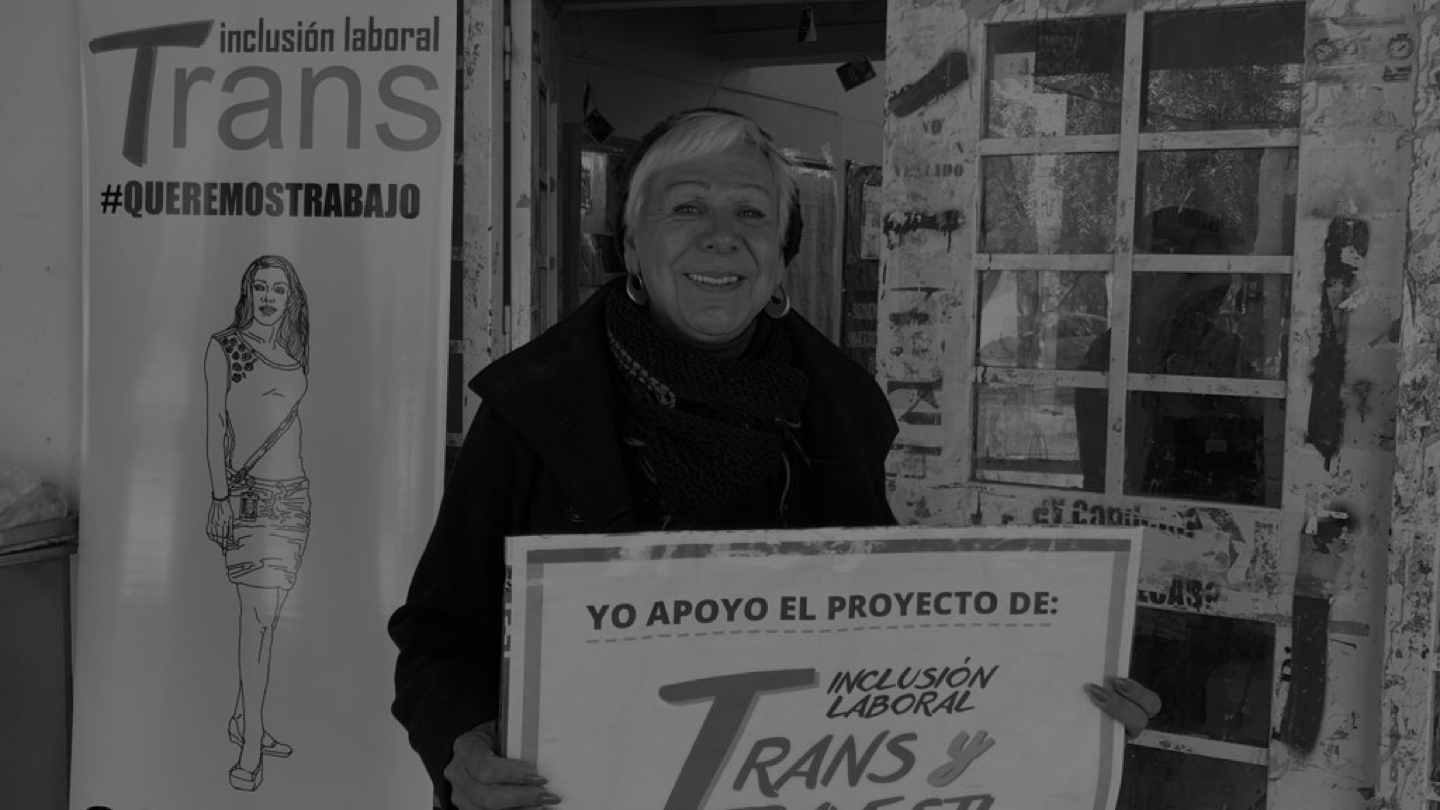

Leona Freitas is the typical woman of a Brazilian inner city. She rarely ventured out Congonhas, where she was born and works, and has never visited the big city. São Paulo is a distant dream for her. Belo Horizonte, capital of the state in which she lives, distant only 80 km from her hometown, is only a wish. “Whenever I go,” she says.

The tiny historic town is known for its religious festivals, which attract thousands of Catholic faithful from all over the country. With its countless churches and Christian schools, Congonhas is the portrait of South America: religious and conservative.